You’ve probably been here before.

Your organisation has architects. Maybe even good ones. Business architects are mapping capabilities. Data architects are defining governance models. Security architects are reviewing designs. Technology architects are setting standards and reference architectures.

Everyone’s busy. Everyone’s producing artefacts. Governance forums are running. Reviews are happening.

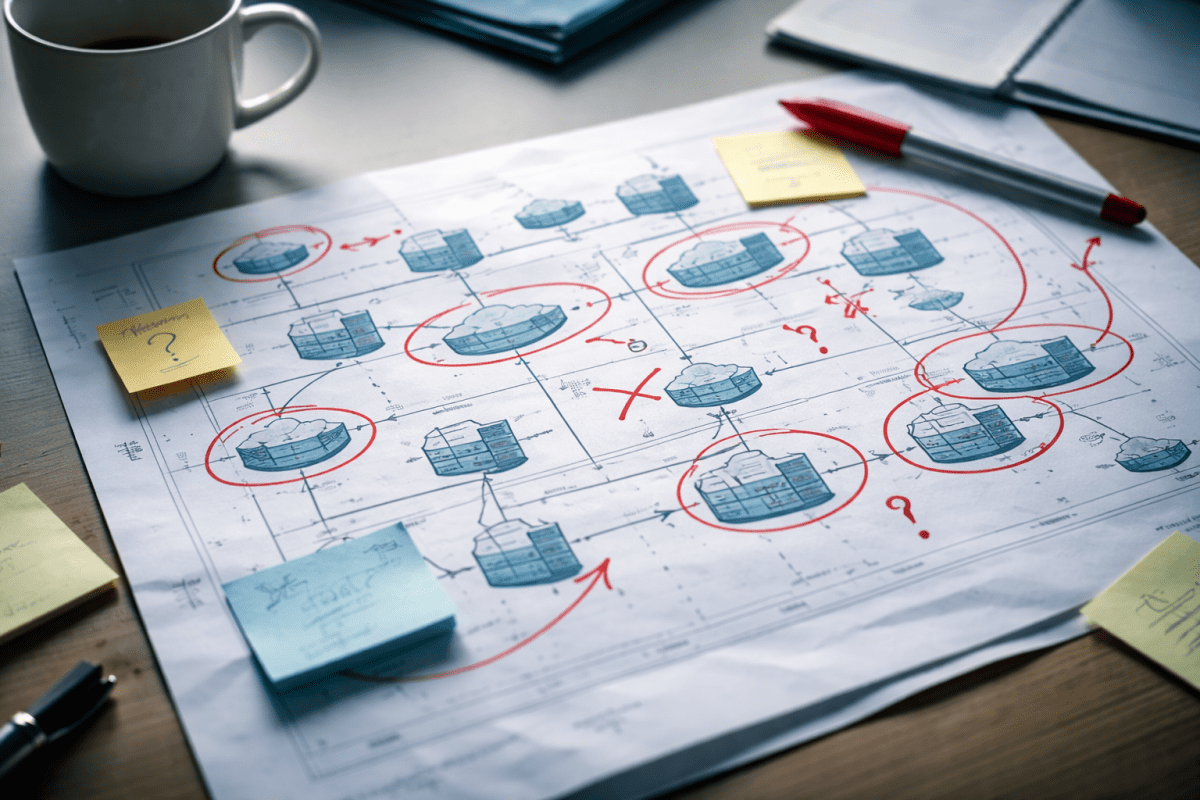

And somehow, a project that’s been in flight for six months gets blindsided by an integration issue that should have been caught in week two. Strategic intent — the thing the CIO articulated clearly in the boardroom — gets lost somewhere between the strategy deck and the codebase. Security raises a showstopper finding three weeks before go-live. Technical debt accumulates faster than anyone can track, let alone manage.

If this sounds familiar, you’re not alone. And the problem probably isn’t what you think it is.

It’s Not a Talent Problem

When architecture consistently fails to prevent these scenarios, the instinct is to question capability. Do we have the right people? Do they need more training? Should we hire more senior architects?

Sometimes the answer is yes. But more often, the architects you have are perfectly capable. They’re just operating in a structure that makes connected outcomes nearly impossible.

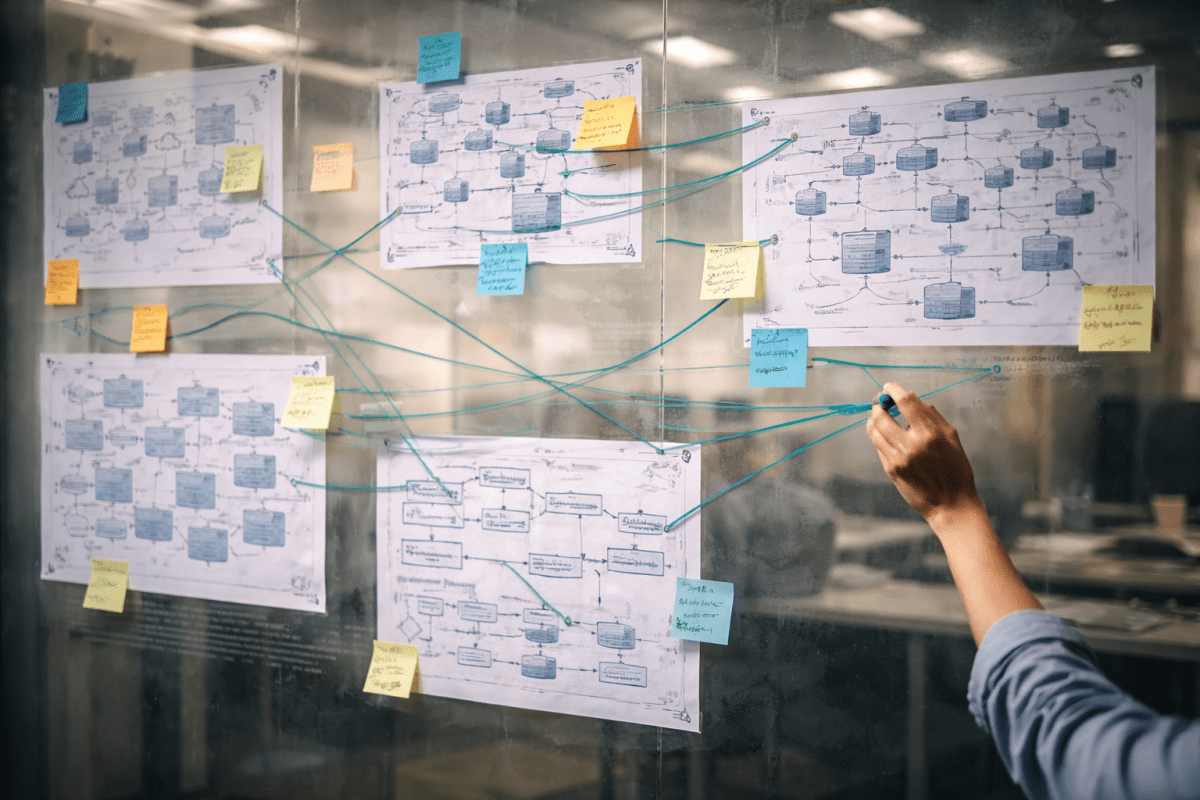

Think about how most architecture functions actually work day-to-day. Business architecture produces capability maps, value streams, and strategic alignment artefacts. Technology architecture produces reference architectures, standards, and platform roadmaps. Security architecture produces threat models, control frameworks, and design reviews. Data architecture produces data models, governance policies, and lineage documentation.

Each domain is doing good work. Each domain has its own governance rhythm, its own artefact standards, its own stakeholder relationships. The problem is what happens — or more precisely, what doesn’t happen — between them.

The Gap Between Domains

In most organisations, architecture domains coordinate through two mechanisms: governance forums and informal relationships.

Governance forums — your architecture review boards, design authorities, and steering committees — are where domains come together periodically to review work. They’re useful, but they’re fundamentally reactive. By the time something reaches a governance forum, decisions have already been shaped. The forum ratifies or challenges, but it rarely catches the upstream disconnection that created the problem in the first place.

Informal relationships are the other mechanism, and in many organisations, they’re the more effective one. The business architect who happens to have a good working relationship with the security architect will naturally share context, flag concerns early, and align their outputs. This works brilliantly — until one of them moves on to another role.

Neither mechanism creates systematic connection between domains. Business architecture outputs don’t automatically become technology architecture inputs. Security considerations don’t embed at every layer of the traceability chain — they get assessed at the end, when changing direction is expensive. Data architecture operates in its own governance model that may or may not align with how the technology architects are thinking about platform decisions.

The result? Comprehensive documentation and disconnected execution.

What Disconnection Actually Costs

The cost of disconnected architecture isn’t always dramatic. It’s not usually a single catastrophic failure (though those happen too). It’s the steady accumulation of friction, rework, and missed opportunities that compounds over time.

Integration surprises. A solution architecture passes technology review but nobody mapped it against the data architecture’s lineage requirements. Six weeks into build, the integration team discovers data flows that violate governance policies. Rework, re-review, re-plan.

Security as a gate instead of a partner. When security architecture operates as a separate review function rather than an embedded concern, projects experience the “department of no” effect. Findings arrive late. Remediation is expensive. Teams learn to avoid early engagement because they associate security review with delay, creating exactly the dynamic everyone wants to prevent.

Strategic intent evaporation. The CIO communicates a clear strategic direction. Business architecture translates it into capability priorities. Technology architecture sets platform direction. But the translation between these layers isn’t systematic, so by the time decisions reach solution design, the connection to strategy is tenuous at best. Six months later, the CIO asks why the technology portfolio doesn’t reflect the strategy they articulated, and nobody has a clear answer.

Technical debt you can’t see. When domains don’t share a common view of architecture decisions and their rationale, debt accumulates invisibly. Decisions that make sense within one domain create downstream impacts in others that only surface during implementation — or worse, during production incidents.

Knowledge that walks out the door. When connection between domains depends on individual relationships rather than systematic practice, your architecture capability is as fragile as your retention rate. Every departure takes context, rationale, and relationships with it.

Why Most Frameworks Don’t Fix This

If you’ve looked at this problem before, you’ve probably looked at frameworks. TOGAF. Zachman. FEAF. SAFe’s architecture runway. They all describe what architecture should look like. They define domains, artefacts, and governance concepts.

What they generally leave to individual interpretation is the practical mechanics of connection. How do business architecture outputs become technology architecture inputs? Where does security embed in the traceability chain? What governance model scales scrutiny proportionally to risk instead of applying the same heavyweight review to everything?

These are implementation questions, and most frameworks treat them as “adapt to your context” exercises. Which is fair enough — context matters. But it means the hardest part of architecture — the connective tissue between domains — is exactly the part with the least guidance.

You end up with a well-defined framework and a disconnected practice. The framework becomes the documentation standard. The actual architecture work still happens in domain silos, coordinated by governance forums and heroic individual effort.

There’s a Different Way to Think About This

What if connection wasn’t something you had to engineer through coordination effort, but something that was designed into the framework from the start?

What if you started with the governance foundations — decision records, oversight models, guardrails — and then plugged in domain capability as you needed it, with each domain inheriting the same connective tissue?

What if strategy traced to capability traced to information traced to technology traced to solution, not because someone manually maintained the links, but because the framework made traceability the default?

That’s the thinking behind XAF Connected Architecture. It’s a framework we built after years of watching talented architecture teams produce excellent domain-specific work that didn’t connect, in organisations that had invested heavily in frameworks that defined what architecture should look like but left the practical mechanics of integration to chance.

XAF takes a different starting point: governance first, domains second, connection by design rather than by heroic effort. It’s modular, so you start with what you need and scale to what you grow into. And it’s practical — designed for architecture teams that need to deliver value, not just produce documentation.

If the patterns in this post resonate — if your architecture domains are busy but not connected, if your governance forums are reactive rather than preventive, if your architecture knowledge is fragile because it depends on individual relationships — then the problem isn’t your people. It’s your connective tissue.

And that’s a solvable problem.

This is the first post in a series exploring XAF Connected Architecture — what it is, why we built it, and how to implement it. Next up: What Is XAF Connected Architecture? A Practical Alternative to Framework Overload.

Ready to explore whether your architecture practice has a connection problem?

Todd Johnson is the creator of XAF Connected Architecture and founder of InnovateX Solutions, a Queensland-based IT consulting firm specialising in enterprise architecture, cybersecurity, and digital transformation for government and enterprise clients.